Materialsammlung

mīgozarād [it will pass]

written on a teahouse-wall in Kunduz

“I maintain the principle that the duration of peace stands in direct proportion to the slaughter of the enemy. The harder you strike them, the longer they will hold on”

General Skobelev/Russia (commanded the massacre of the Turkmen fortifications at Göp-Teke in 1881. He allowed his troops to pillage and plunder for three days. 15,000 defenders and their families were slaughtered.)

What defines an individual without connections? The definition comes from a daily reality continually occupied by the impossibility of travel and the successive fractures of love, by the utopia of reconstruction and cohabitation with horror, by the inexistence of the future and the violation of citizenship, by the death of dreams and the corrosion of objects, by the exhaustion of hope and the dismanteling of the group, the fragmentation of the body and the insularity of language. The persistence of war through bombs, mines, traumas, abandonment, isolation, pain, hatred, indigence, hunger, ignorance and fear makes it seem that the marrow of the human condition has been mortally wounded and the mankind has begun to reproduce a vacuum in their own genetic memory. God remains out there somewhere – perhaps with even greater strength given the impotence of his people in the abyss – but the lines of communication have also been cut, along with all the calendars and rites of communion.

For centuries, diverse powers and spheres of interest have clashed in Central Asia. With the discovery of huge oil and natural gas deposits, the “Great Game” for dominance in this key geopolitical zone became a struggle in which violence is commonplace and the outcome of which is unforeseeable. The stakes are rule and control, regional autonomy and central power. Also at stake is hegemony, advantage in the exploitation of mineral wealth and in the construction of transport systems to handle it.

Estimates vary, but there is no question that, after the Persian Gulf, the region around the Caspian Sea is one of the largest oil-bearing zones in the world. Ethnic and religious diversity is both a cause and a consequence of numerous conflicts here. The “large scale” struggle for raw materials is overlaid by many “small-scale” disputes, some of which are very tribal feuds. Domino: large conflicts are sparked by small ones, and small conflicts escalate into major ones. So there is nothing romantic about pipelines. But for the part of the world being considered for this reportage, they are the modern equivalent of the Silk Road. The only exports that could bring hard currency into the region quickly are petroleum and natural gas.

Irregular borders, as well as overlapping areas of settlement sprinkled with enclaves or exclaves, bear witness to wars, deportation and destruction. Within the zone extending from the Caucasus to the Hindukush is an accumulation of the old burdens left behind by the Russian, Ottoman and Persian empires, and, the more recent, still-unhealed wounds inflicted by the Soviet Union. Political boundaries, often drawn by military might, devoid of all reasons and straight across ethnic-cultural structures, are one of the leading causes of conflict. It is no easy matter to distinguish between rebellion and a legitimate striving for autonomy, between banditry and police action, peacekeeping and peace enforcing, genocide and aggression: judgements call for a high degree of knowledge.

In the present confrontation -the playing field- has widen, northwards and eastwards, includes now Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Pakistan, from that of the original Great Game, Afghanistan. Local and global players are searching for ways to bring those precious commodities to international markets while keeping Russia and China from new geopolitical positions. It would be a major error to see the Great Game and its prize exclusively in the classic terms of securing raw materials and markets, the categories in which the industrial powers thought until World War II. Even back then it was true only up to a certain point that getting a grip on a geographic area automatically gave one an advantage over others. Under the conditions of todays globals economy, it has become even less true. Oil, cotton and other commodities can be bought, if one´s own productivity in other areas is secured by technology and ideas.

But when a region is landlocked, as Central Asia is, when rivals prefer to flex their muscles rather than engage in open competition, when local rulers make their dispositions primarily on the basis of political preference or personal advantage – then the principle of geopolitics which states that, where one party is already present others cannot so easily go, becomes interesting once again.

Afghanistan never had the kind of nationalization movement that can shape a common identity. „Afghanistan has been, and remains, a tribal society“ says Azade-Ayse Rorlich, professor of history at the University of Southern California. „The undercurrent … is an enormous fragmentation unmatched by anything in Central Asia.“ Still, the tribes have one thing in common: a passionate distaste for foreign/ers/armies of any kind.

„And then you will build a house,

a tall house of stone …

you send your children to school.

They are to learn and to become whole human beings.

It will be a good, proper school

for everything will be good and proper.

Work gives bread and the law freedom.

Is it not what it is about,

Don´t we all want that?

You go home

And will never be a slave again.

Neither you nor your children.“

Slawomir Mrozek, „Emigrants“

Given these conditions in its immediate environment, it is uncertain how long the people of the region will be able to remain if the Great Game continues to be played. In Central Asia it has not been the first war fought over oil and the access to gas. It is unlikely to be the last.

Animation 60|60

…

Aufgrund seines schwebenden Charakters durchströmt die Fläche wie eine Membran den Raum. Es übersetzt die natürlichen und menschgeschaffenen Gewalten der Region konträr in eine verstörende Leichtigkeit. Sie verhält sich zunächst neutral zum umgebenden Raum, lässt diesen aber zusammen mit den realen Körpern der Anwesenden zum imaginären Resonanzraum des sinnlich Abwesenden werden. Metaphorisch greift die Fläche das kosmologische Motiv einer ewigen Wiederkehr auf, wie es sich schon bei Heraklit findet:

„Und es ist immer ein und dasselbe, was in uns wohnt: Lebendes und Totes und Waches und Schlafendes und Junges und Altes. Denn dieses ist umschlagend jenes und jenes zurück und umschlagend dieses.“

…

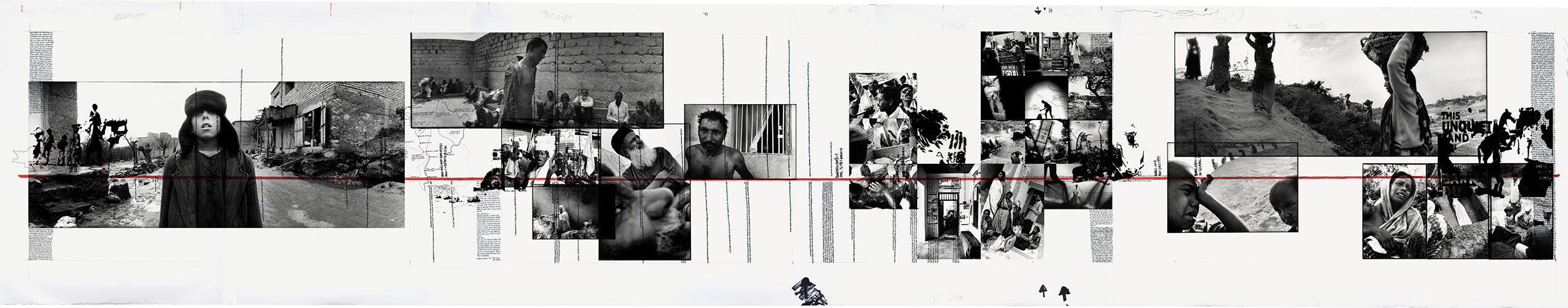

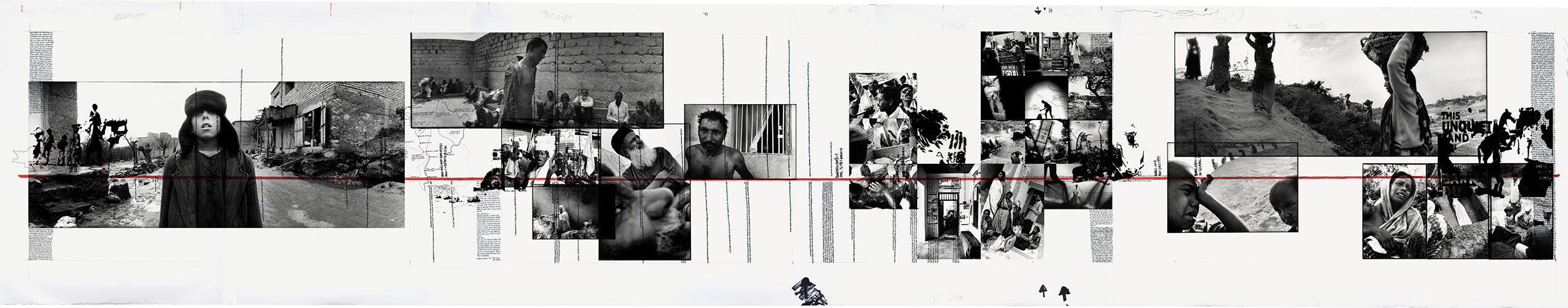

first draft for “troubled shores”

first draft for “troubled shores”

Along the Grand Trunk Road

Twelve diary entries for our travel pages

“

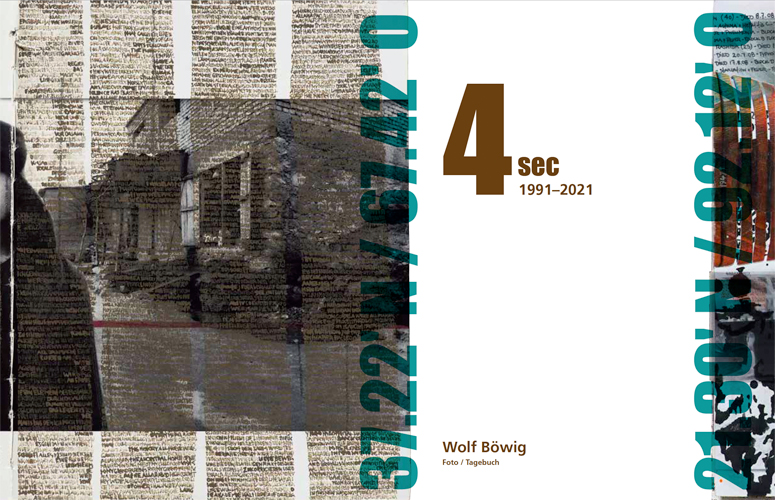

Wolf Böwig is a photojournalist, a war reporter who travels to the places that other people are leaving in droves. Euphemistically, he refers to them as conflict regions, but the horrors he encounters far surpass anything the term ‘conflict’ could possibly evoke. He covered the Yugoslav wars and the war in Afghanistan, and he was in Africa immediately after the Rwandan genocide. It is no accident that these are all corners of the world where the borders have been arbitrarily drawn and do not coincide with cultural, historical or ethnic areas, which, in turn, is one of the reasons why there is little trust in the state in these regions.

What Böwig saw and experienced in his travels often resembled scenes from a nightmare, and consequently his photographs regularly take us to the limits of what we can bear, and many go even further. What drives him, Böwig says, is a humanist mission which he has taken upon himself. He is not after the spectacular single image. Instead, he has been returning to many places every year for long-term reporting, and he has accompanied some people for a good part of his life. He used to work for Neue Zürcher Zeitung, for Le Monde and the New York Times, but there is no place in daily news journalism anymore for an approach like his. Now Böwig concentrates on producing and contributing to exhibitions, brochures and book projects, visual indictments through which he wants to raise awareness for the inhumanity of everyday life in the world’s warzones. In 2017, his last journey to date led him along the Grand Trunk Road from the Myanmar border through Bangladesh, India and Pakistan all the way to Kabul.

Böwig travelled along this route for five months on buses, by bicycle or on foot, not as a tourist, but as an observer, looking for the traces of economic, political and religious conflicts 70 years after the Partition of the subcontinent. He brought not much more than the clothes he had on, two cameras, three objective lenses, bags full of films, and the small tools for his diary: scissors and glue. From the little things that he found along the way and that seemed significant, Böwig produced collages which he collected in a folder. His materials were coins, photographs, newspaper clippings, matches and packaging, razor blades and pebbles. These collages are an artistic way of processing what he experienced, full of symbols and metaphors. Notes about his impressions complete the collages. Böwig calls these works a ‘departure for the inside’. Producing them is his personal method for finding calm at the flashpoints of world politics. Over the course of this year, twelve of these collages will be featured on our travel pages on double-page spreads, to retell Böwig’s journey three thousand kilometres from East to West across the entire subcontinent.

“

FAZ, 11. January 2018

SIGNUM MORTIS

“

The northern part of the Balkans, former Yugoslavia, its successor states: Into this region, the documentary artist Wolf Böwig has undertaken numerous travel reportages since the 1990s, most recent for his project „Signum Mortis“ in March and April 2019. Thereby, he has collected a hugh archive of images, sketches, diaries, collages, and impressions that represents the catastrophic political and social transformations of this region during the last quarter of a century: wars, inter- and inner-ethnic conflicts, reconstruction, forced migration.

The various elements of „Signum Mortis“, covering different areas of Southern Europe over a time span of more than 25 years, are hold together by the perception of Wolf Böwig as a documentary photographer and a travelling artist who gets immersed into the scene he wants to document. As an eyewitness his impressions are framed by an excellent knowledge about the literature and culture of the region. And he comes back home with always the same question: Why?

„Signum Mortis“ follows Böwig’s travel itinerary, including emblematic places like Jasenovac, Popovac (Croatia), Belgrad (Serbia), Visegrad (Bosnia), Pristina (Kosovo) und Gevgelija/Idomeni (Macedonia/Greece). His images are accompanied by texts from Marko Dinić, Habbo Knoch, and Pedro Rosa Mendes.

Thus, „Signum Mortis“ works like an assemblage. It’s multi-perspective approach will open new vistas on a ridden landscape and its people. It tries to de- and reterritorialize images of the region – it resonates how morality, humanity, and solidarity have been ruined and how these wounds are still visible under a surface of apparent normality.

“

Habbo Knoch

BLACK.LIGHT PROJECT

„Death in the Shadows“

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 14. January 2012

Andreas Platthaus

“

At the beginning of 2011, everything appeared to be going well, both with the project and the financing. Things were progressing quickly, and, upon first glance, “Black.Light” looked even better than one could have expected a year ago. But now there’s money trouble, even though 10 leading illustrators are currently working on “Black.Light.”

It’s so typical: Initially, leading artists and journalists are quick to show an interest for the desperation in the world’s nether regions. They develop a concept to bring together not only the most disparate forms of storytelling, but also people from north and south, from wealth and poverty, from light and shadow. Then, out of nowhere, the genesis of something spectacular suddenly draws the focus of attention and the financial means to something much more appealing, because we prefer to document beauty instead of ugliness, to show that which puts us in a good light instead of what our shadows are. Now, there is no more interest in “Black.Light” because that something spectacular is last year’s Arab Spring. But what does it have to do with Black.Light?

First, one has to ask: What is Black.Light? Simply posing the question speaks volumes about the problems of the project. Normally, one would think a cross-border and cross-discipline concept for presenting human tragedy through a combination of artistic and documentary styles would stir interest and attract support. But during the time in which the tragedy played out – 1989 to 2007 – it was given short shrift outside of Africa. Fighting in the successor states of Yugoslavia, the Middle East conflict and two Iraq wars were more than just competition for publishing space: They made the West blind to the horrors in regions that are merely on the periphery of its spheres of interest. So much is true for areas like West Africa.

From 1989 to 2007, Charles Taylor defined life in that part of the world. The Liberian warlord carried the power struggle for his homeland to neighboring states before actually becoming president of Liberia following the 1997 civil war. Once in office, he fomented a second civil war and further international conflicts. International pressure forced his resignation in 2003, he was extradited from his exile in Nigeria in 2006, and in 2007 he found himself charged with war crimes in Sierra Leone by a U.N. Special Court in The Hague. The trial against the man who once set West Africa aflame in still underway. Black.Light tells the story of the effects of Taylor’s actions.

…

“

![]() Read full story at Melton Prior Institut for reportage drawing & printing culture

Read full story at Melton Prior Institut for reportage drawing & printing culture

Bildauswahl LTP

SIGNUM MORTIS

“

Der nördliche Balkan, das ehemalige Jugoslawien, dessen Nachfolgestaaten: Dort hat der Fotograf Wolf Böwig seit Anfang der 1990er Jahre wiederholt umfangreiche Reportagereisen unternommen, zuletzt im März und April 2019. So ist ein Archiv aus Bildern, Skizzen, Tagebüchern, Collagen und Eindrücken entstanden, in denen sich die gravierenden politischen und gesellschaftlichen Veränderungen dieser Region im vergangenen Vierteljahrhundert widerspiegeln: die Kriege, die nationalen und ethnischen Konflikte sowie der Wiederaufbau bis hin zur jüngsten Flüchtlingskrise.

Doppelheft und Ausstellung verstehen sich als eine erweiterte Dokumentation dieser Reportagereisen in den Südosten Europas. Ihr roter Faden ist der Reisende, in die Orte dieser Region eintauchende Fotograf. Der Augenzeuge vertieft seine Wahrnehmungen durch eine vielseitige Kenntnis der Literatur zu dieser Region und ihren Konflikten. Und kehrt immer wieder mit der Frage zurück: Warum?

Der Aufbau ist wie eine Reiseroute gestaltet, die um emblematische Orte kreist: Jasenovac, Popovac (Kroatien), Belgrad (Serbien), Visegrad (Bosnien), Pristina (Kosovo) und Gevgelija /Idomeni (Grenze Mazedonien/Griechenland).

Die Fotografien werden um Collagen des Fotografen, Texten von Ivona Grgurinović, Marko Dinić, Habbo Knoch, Pedro Rosa Mendes und Skizzen von David von Bassewitz erweitert. Sie bilden eigene Perspektiven, um sich der Region zu nähern.

Das Ergebnis ist eine Assemblage – eine Verbindung aus verschiedenen Zugängen, die neue Perspektiven auf die Räume der Gewalt und deren Verarbeitung eröffnen. Sie reterritorialisieren Landschaften im Bewusstsein der Betrachter, indem Orte, Grenzen und Routen über die Zeiten hinweg oszillieren – wie eine Resonanz auf die Zerstörung der Moral in den Kriegen der 1990er Jahre und deren bis heute ungeheilte Wunden.

“

Habbo Knoch

What defines an individual without connections? The definition comes from a daily reality continually occupied by the impossibility of travel and the successive fractures of love, by the utopia of reconstruction and cohabitation with horror, by the inexistence of the future and the violation of citizenship, by the death of dreams and the corrosion of objects, by the exhaustion of hope and the dismanteling of the group, the fragmentation of the body and the insularity of language. The persistence of war through bombs, mines, traumas, abandonment, isolation, pain, hatred, indigence, hunger, ignorance and fear makes it seem that the marrow of the human condition has been mortally wounded and the mankind has begun to reproduce a vacuum in their own genetic memory. God remains out there somewhere – perhaps with even greater strength given the impotence of his people in the abyss – but the lines of communication have also been cut, along with all the calendars and rites of communion

Ukraine, Serbia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Bosnia, Croatia, Greece

For access to the entire reportage (images and text) please contact Wolf Böwig

Auf der Grand Trunk Road:

Zwölf Kapitel eines Tagebuchs als Schlussseite des Reiseblatts

“

Wolf Böwig ist Fotojournalist, ein Kriegsreporter, der an Orte reist, während andere sie gerade in großer Zahl verlassen. Beschönigend spricht er von Konfliktregionen. Doch das Grauen, dem er begegnet, überbietet alles, was die Vokabel Konflikt in sich versammeln kann. Er war im Balkankrieg, im Afghanistankrieg und in Afrika unmittelbar nach dem Genozid in Ruanda – nicht zufällig allesamt Weltgegenden, deren Grenzen willkürlich gezogen sind und sich kaum je mit kulturell, historisch oder ethnisch geprägten Räumen decken und in denen es nicht zuletzt deshalb an Vertrauen in die Staatsmacht fehlt.

Was er unterwegs sah und erlebte, glich nicht selten den Szenen eines Albtraums. Folgerichtig führen viele seiner Fotografien an die Grenzen des Zumutbaren – und etliche auch darüber hinaus. Ihn treibe, sagt Wolf Böwig, ein selbstgestellter humanistischer Auftrag an. Es ist ihm nicht um das sensationelle Einzelbild zu tun, vielmehr kehrt er für Langzeitreportagen an viele der Orte Jahr um Jahr zurück und begleitet manche Menschen bereits einen Gutteil ihres Lebens. Früher arbeitete er für die „Neue Züricher Zeitung“, für „Le Monde“ und die „New York Times“. Aber im Tagesjournalimus ist für einen solchen Ansatz kein Platz mehr. So konzentriert sich Böwig heute auf Ausstellungen, Broschüren und Buchprojekte: bildgewordene Anklageschriften, mit denen er ein Bewusstsein für den unmenschlichen Alltag in den Krisenherden der Welt schaffen will. Seine vorerst letzte Reise führte ihn 2017 auf der Grand Trunk Road von der Grenze Burmas über Bangladesch, Indien und Pakistan bis nach Kabul.

Fünf Monate war er unterwegs, mit Bussen, auf Fahrrädern oder zu Fuß, nicht als Tourist, sondern als Beobachter, der siebzig Jahre nach der Teilung des Subkontinents Spuren wirtschaftlicher, politischer und religiöser Konflikte suchte. Was er dabeihatte, war wenig mehr als die Kleidung an seinem Körper sowie zwei Kameras, drei Objektive, Taschen voller Filme – und kleines Werkzeug für sein Tagebuch: Leim und Schere. Denn mit dem, was ihm unterwegs von Bedeutung erschien, klebte er Collagen in eine Kladde: Münzen, Fotos und Zeitungsausrisse, Streichhölzer und Verpackungen, Rasierklingen und Steine. Es ist eine künstlerische Auseinandersetzung mit dem Erlebten, voller Symbole und Metaphern, ergänzt um die Niederschrift seiner Eindrücke. Böwig bezeichnet die Arbeiten als einen Ausbruch ins Innere. Es ist seine Form, Ruhe zu finden im Strudel der Weltpolitik. Zwölf Doppelseiten dieser Tagebücher wird das Reiseblatt im Laufe dieses Jahres zeigen und damit Böwigs Reise nacherzählen – dreitausend Kilometer von Ost nach West durch den gesamten Subkontinent. (F.L.)

“

FAZ vom 11. Januar 2018

„

… Neben den Konflikten selbst sind es vor allem deren Nachwirkungen, Spuren und Spätfolgen, die ich zum Thema mache. So überkreuzen sich verschiedene Zeitebenen in meiner Wahrnehmung und Aneignung, die ich in meinen Arbeiten zum Ausdruck bringen möchte: meine eigene Geschichte mit diesen Regionen (introspektiv), die Entwicklung von Konflikt- und Postkonfliktgesellschaften (prospektiv) und die Gleichzeitigkeiten von Gegenwart und Vergangenheit (retrospektiv). …

„

„

… Grenzen jeglicher Art, von geistigen über politische bis hin zu kulturellen, sind von zentraler Bedeutung für Wolfs Darstellung der uns allen gemeinsamen menschlichen Natur. Es ist dieser eingefleischte Irrsinn, den er brutal offenlegt, mit Schichten historischer, politischer, emotionaler und sprachlicher Komplexität. In Wolfs gesamtem umfangreichen Werk zeigt sich die menschliche Realität in Gestalt einer Offenbarung und nur sehr selten einer Entblößung, wobei jeder fotografische Augenblick eine Fülle von Bezügen einfängt, die ein Gefühl individueller, kollektiver und sozialer Identität definieren – Identität als jene höchste Form des Irrsinns hinsichtlich des eigenen Ichs. …

„

Auf der Grand Trunk Road:

Zwölf Kapitel eines Tagebuchs als Schlussseite des Reiseblatts

Wolf Böwig ist Fotojournalist, ein Kriegsreporter, der an Orte reist, während andere sie gerade in großer Zahl verlassen. Beschönigend spricht er von Konfliktregionen. Doch das Grauen, dem er begegnet, überbietet alles, was die Vokabel Konflikt in sich versammeln kann. Er war im Balkankrieg, im Afghanistankrieg und in Afrika unmittelbar nach dem Genozid in Ruanda – nicht zufällig allesamt Weltgegenden, deren Grenzen willkürlich gezogen sind und sich kaum je mit kulturell, historisch oder ethnisch geprägten Räumen decken und in denen es nicht zuletzt deshalb an Vertrauen in die Staatsmacht fehlt.

Was er unterwegs sah und erlebte, glich nicht selten den Szenen eines Albtraums. Folgerichtig führen viele seiner Fotografien an die Grenzen des Zumutbaren – und etliche auch darüber hinaus. Ihn treibe, sagt Wolf Böwig, ein selbstgestellter humanistischer Auftrag an. Es ist ihm nicht um das sensationelle Einzelbild zu tun, vielmehr kehrt er für Langzeitreportagen an viele der Orte Jahr um Jahr zurück und begleitet manche Menschen bereits einen Gutteil ihres Lebens. Früher arbeitete er für die „Neue Züricher Zeitung“, für „Le Monde“ und die „New York Times“. Aber im Tagesjournalimus ist für einen solchen Ansatz kein Platz mehr. So konzentriert sich Böwig heute auf Ausstellungen, Broschüren und Buchprojekte: bildgewordene Anklageschriften, mit denen er ein Bewusstsein für den unmenschlichen Alltag in den Krisenherden der Welt schaffen will. Seine vorerst letzte Reise führte ihn 2017 auf der Grand Trunk Road von der Grenze Burmas über Bangladesch, Indien und Pakistan bis nach Kabul.

Fünf Monate war er unterwegs, mit Bussen, auf Fahrrädern oder zu Fuß, nicht als Tourist, sondern als Beobachter, der siebzig Jahre nach der Teilung des Subkontinents Spuren wirtschaftlicher, politischer und religiöser Konflikte suchte. Was er dabeihatte, war wenig mehr als die Kleidung an seinem Körper sowie zwei Kameras, drei Objektive, Taschen voller Filme – und kleines Werkzeug für sein Tagebuch: Leim und Schere. Denn mit dem, was ihm unterwegs von Bedeutung erschien, klebte er Collagen in eine Kladde: Münzen, Fotos und Zeitungsausrisse, Streichhölzer und Verpackungen, Rasierklingen und Steine. Es ist eine künstlerische Auseinandersetzung mit dem Erlebten, voller Symbole und Metaphern, ergänzt um die Niederschrift seiner Eindrücke. Böwig bezeichnet die Arbeiten als einen Ausbruch ins Innere. Es ist seine Form, Ruhe zu finden im Strudel der Weltpolitik. Zwölf Doppelseiten dieser Tagebücher wird das Reiseblatt im Laufe dieses Jahres zeigen und damit Böwigs Reise nacherzählen – dreitausend Kilometer von Ost nach West durch den gesamten Subkontinent. (F.L.)

FAZ vom 11. Januar 2018