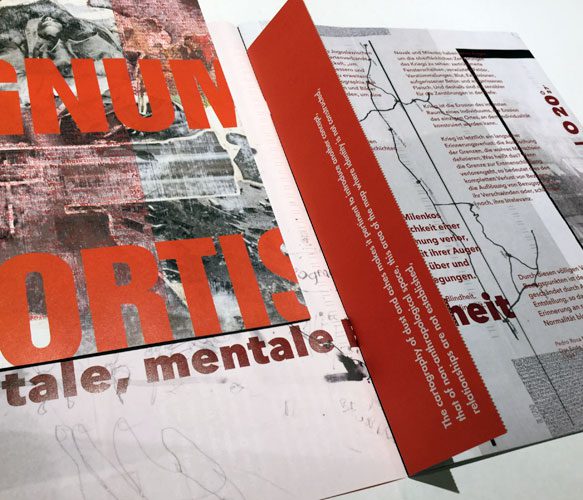

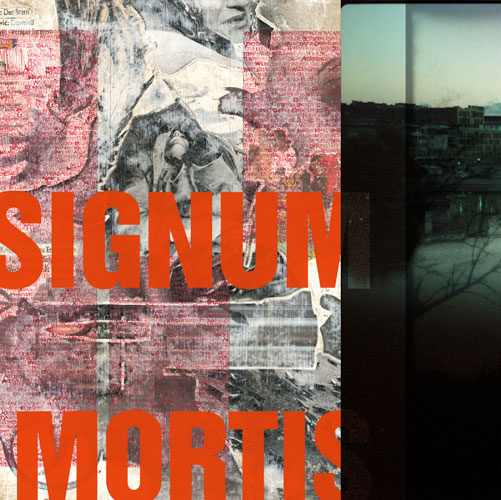

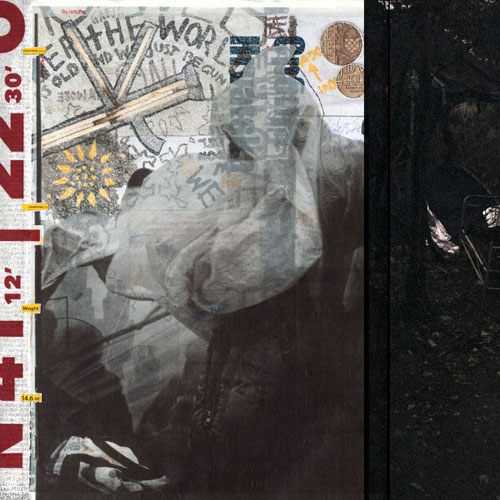

SIGNUM MORTIS

“

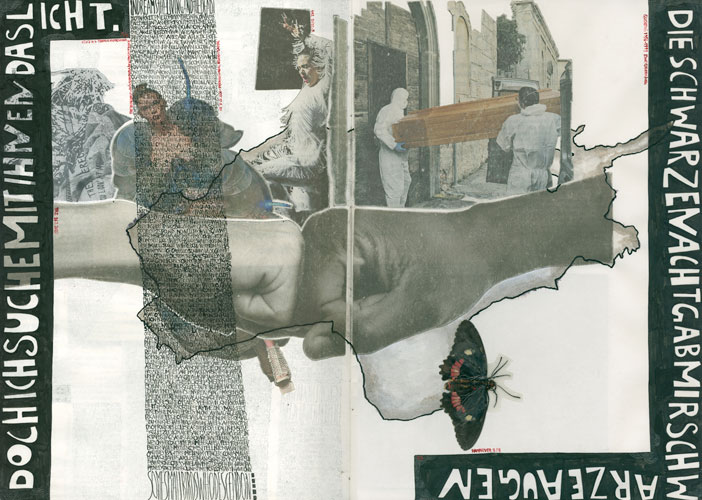

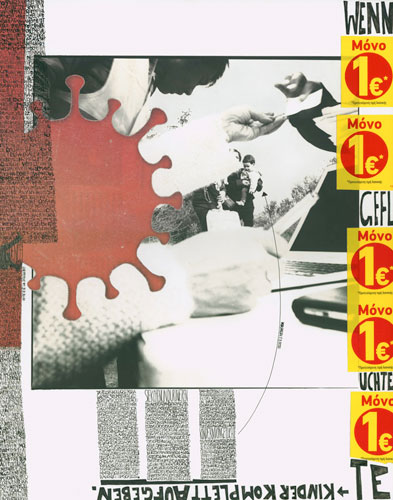

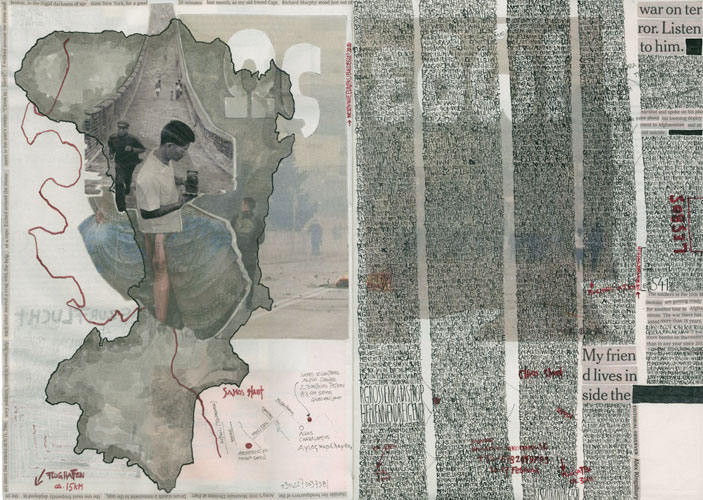

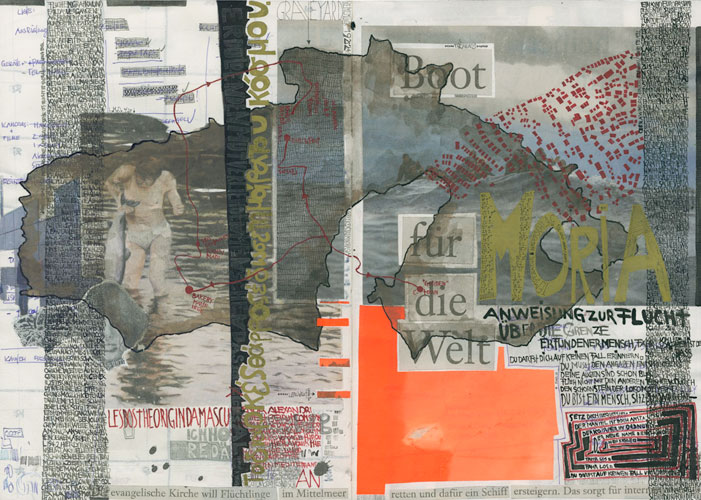

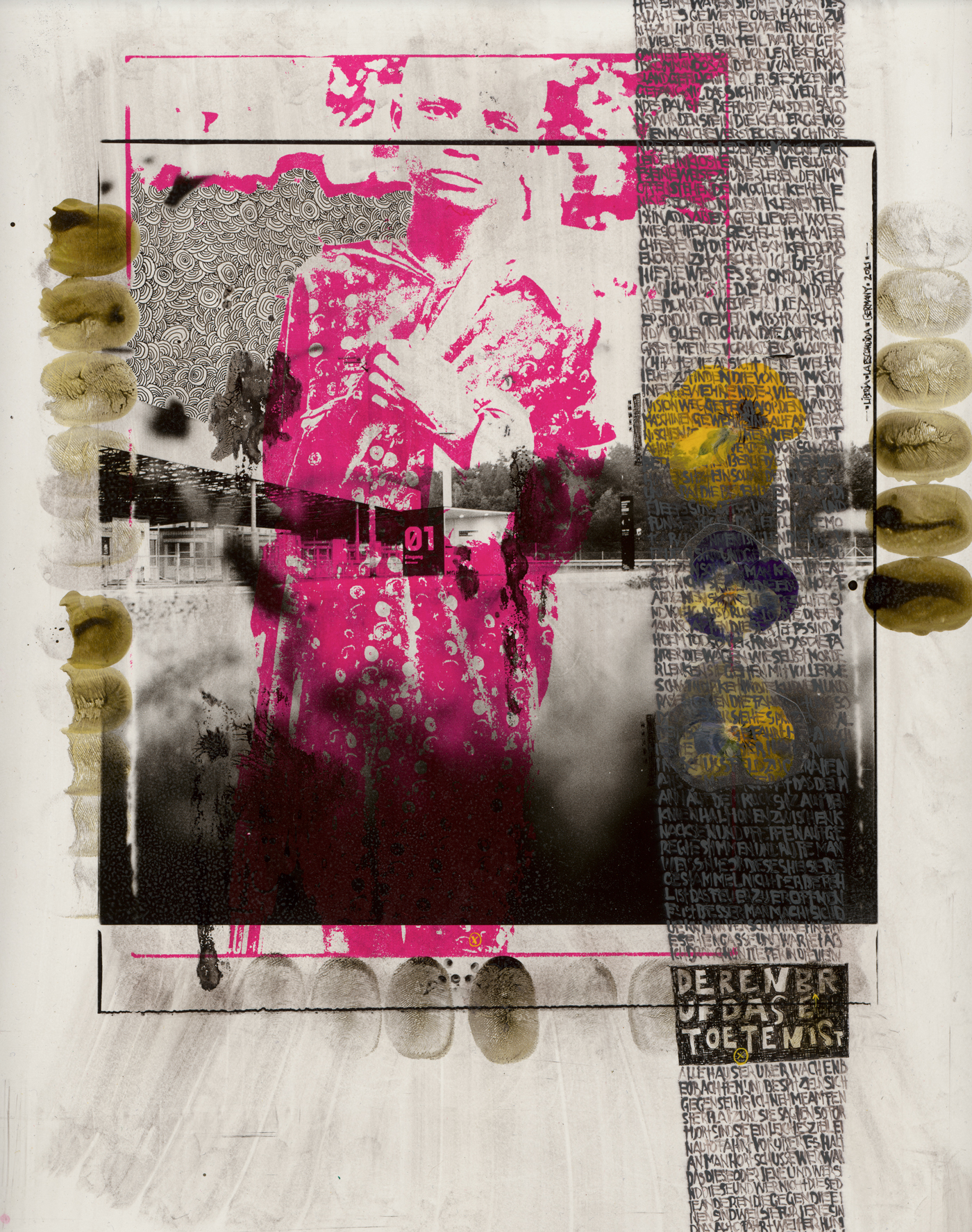

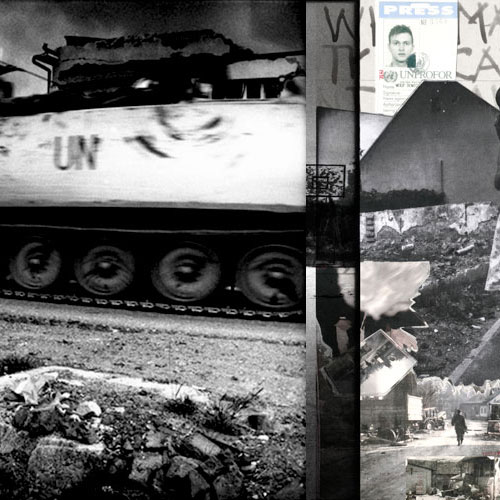

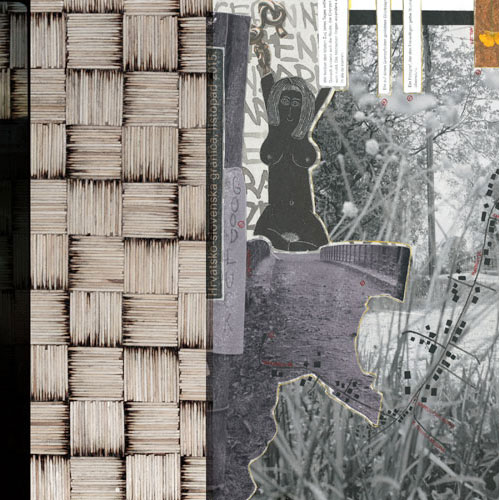

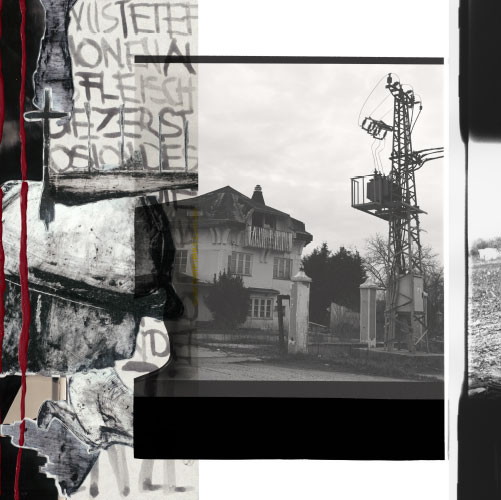

The northern part of the Balkans, former Yugoslavia, its successor states: Into this region, the documentary artist Wolf Böwig has undertaken numerous travel reportages since the 1990s, most recent for his project „Signum Mortis“ in March and April 2019. Thereby, he has collected a hugh archive of images, sketches, diaries, collages, and impressions that represents the catastrophic political and social transformations of this region during the last quarter of a century: wars, inter- and inner-ethnic conflicts, reconstruction, forced migration.

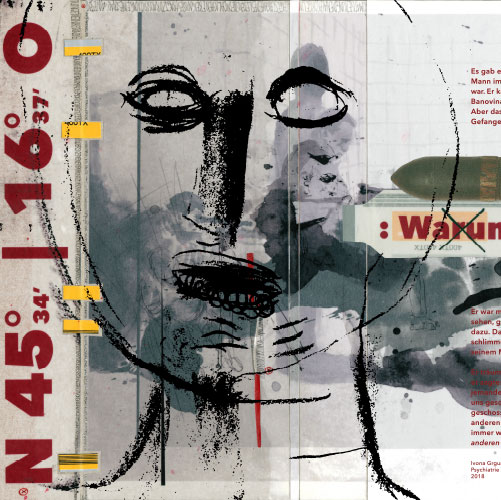

The various elements of „Signum Mortis“, covering different areas of Southern Europe over a time span of more than 25 years, are hold together by the perception of Wolf Böwig as a documentary photographer and a travelling artist who gets immersed into the scene he wants to document. As an eyewitness his impressions are framed by an excellent knowledge about the literature and culture of the region. And he comes back home with always the same question: Why?

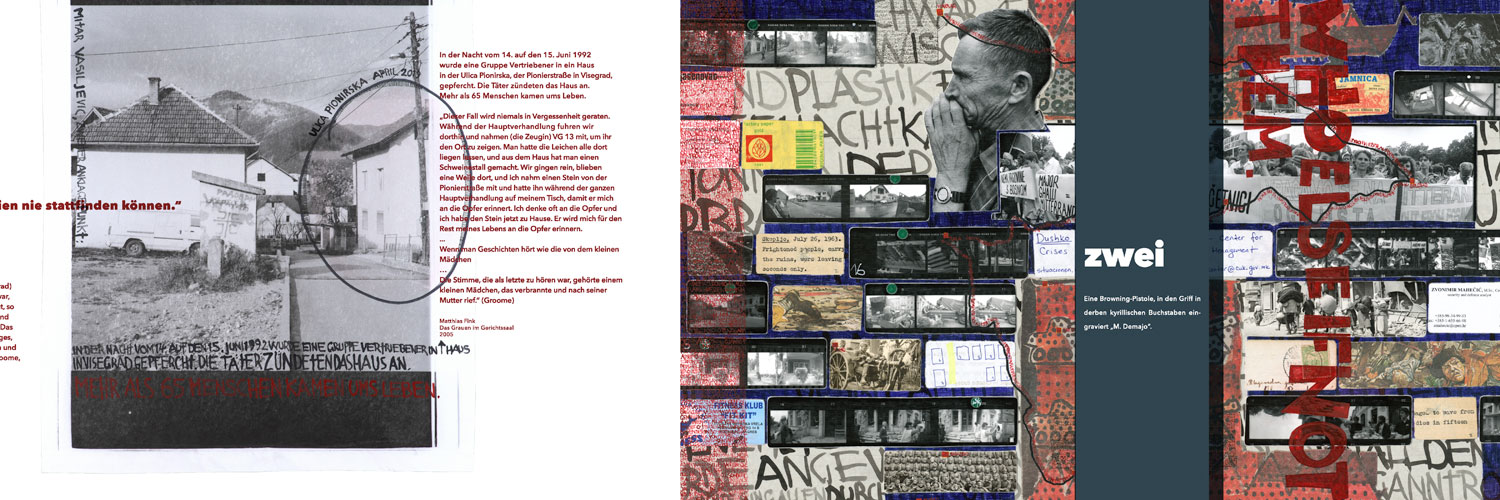

„Signum Mortis“ follows Böwig’s travel itinerary, including emblematic places like Jasenovac, Popovac (Croatia), Belgrad (Serbia), Visegrad (Bosnia), Pristina (Kosovo) und Gevgelija/Idomeni (Macedonia/Greece). His images are accompanied by texts from Marko Dinić, Habbo Knoch, and Pedro Rosa Mendes.

Thus, „Signum Mortis“ works like an assemblage. It’s multi-perspective approach will open new vistas on a ridden landscape and its people. It tries to de- and reterritorialize images of the region – it resonates how morality, humanity, and solidarity have been ruined and how these wounds are still visible under a surface of apparent normality.

“

Habbo Knoch

GRANTS

Grenzgänger scholarship, Robert Bosch Stiftung, 2019

VG Bild publication 2018

Her days were numbered

Pedro Rosa Mendes

I. Resurrection

“Our days are numbered”, Grandmother would tell me whenever I sought her comfort against the pains of life, “Day One is the date you earn your truth”.

In January 1942, the Germans moved a group of women and children from Šabac to the camp in Staro Sajmište. All men and boys had been shot before. They were all part of the Jews from Kladovo: a larger group of Jews that got onboard the boat Uranusfrom Vienna in end-November 1939, down the Danube. Their plan was to reach Sulina, and from there, Haifa. The group later moved onto four ships of the RTC (the Yugoslav River Transport Company), and entered the port of Kladovo on 10 December 1939, taking shelter for winter after calling in Vukovar and Belgrade for coal.

They never made it to Eretz Israel. Backdoor manoeuvers from the Chamberlain Government -loyal to a policy of appeasement with the Arab nations that kept Jews from getting to Palestine- prevented the ship Hilda to ever get to Sulina. The Jews coming from Vienna were still stuck in Kladovo when Hitler occupied Yugoslavia. They were first moved to Šabac, then by train from there to Ruma. From Ruma to Zemun, women and girls were forced to walk in the freezing cold, weakened by hunger and beatings

“The Germans saved me, though”, my grandmother Rahel told me last month, not long before she died, at the age of 96. Rahel, then a little girl of four or five, was among that group. She was “saved” in the sense that she was discarded from the miserable column, in peculiar circumstances. After the group left Ruma to Zemun, someone shot at the Jewish prisoners from the fields. “One shot only”. If Rahel was not the target, she was the victim: the bullet stroke her in the lower back, “and there it stayed”. The prisoners kept on; Rahel was left behind, for dead. Someone took the child back to Ruma and deposed her in front of the church. Grandma told me she believed that it was the priest in the local catholic parish that took her in, got her to be assisted in the hospital, and discretely sponsored her care and education, even after the war, when Rachel was given to a foster family.

It’s a total, mental blindness

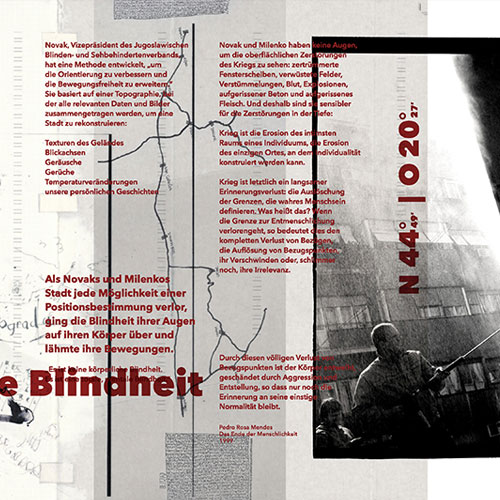

„Novak, vice-president of the ‚Yugoslav Association of the Blind and Seing Impaired’, das devised a techniquewhich „teaches one how to improve orientation and enhance mobility“. It is based on a topography that compiles all the relevant data and images to reconstructa city: textures (…), angles (…), sounds (…), smells (…), variations in temperature (…), our personal histories (…). When Novak and Milenko’s city lost its bearings, the blindness of their eyes infiltrated their bodies and paralysed their movements. It’s not a physical blindness. It’s a total, mental blindness.

Novak and Milenko have no eyes to see the surface of the war: shattered windows, fields laid waste, mutilations, blood, explosions, concrete and flesh splitting apart. For this reason they are more sensitive for the devastation of its depths: war is an erosion of the individual’s most intimate space, the erosion of the one place in which individuality can be constructed (…). War is ultimately a gradual loss of oblivion: the obliteration of the boundaries that define the true human condition. What does this mean? The lost boundary of dehumanisation can be characterized as a complete loss of references, that is a confusion of reference points, their disappearance, or worse, their irrelevance. (…) Given this complete loss of reference points, the body (…) has been desecrated by aggression and adulteration, leavingbehind only the memory of its former normality.“

Pedro Rosa Mendes, The End of Humanity

II. Death

The day after my grandmother’s funeral, I received a small sandalwood box accompanied of a short handwritten note: “May the ashes free the truth. Day One. Yours, always, R.”

The box contained five objects:

One. An old three-striped flag, red-yellow-violet from top to bottom, with a three-pointed red star in the middle yellow stripe. That was the flag of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. To the right of the red star, it bears the handwritten word “Belchite, Aragón”.

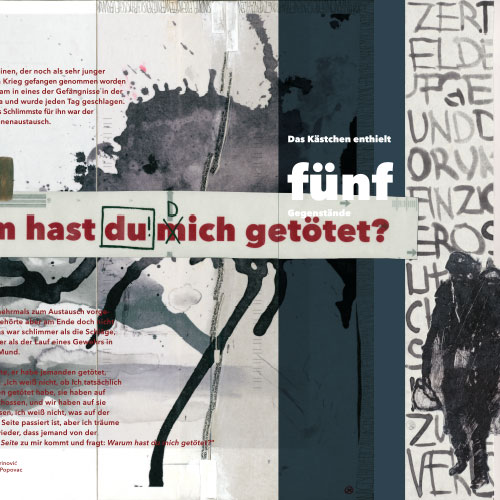

Two. A Browning pistol, with “M.Demajo” engraved in rough Cyrillic characters in the grip.

Three. A drawing by a child, representing some houses in ruins, and four planes above, dropping bombs. A few persons sleeping, or dead. Horizontal, anyway. On the back of the paper, handwritten in the same calligraphy, “Bombardeo de mi Pueblo en Brunete” and “Ruma, Feb.42”.

Four. A few pages of an issue of Dimitrovac, a bilingual newspaper published during 1937 in both Serbo-Croatian and Spanish. The Dimitrovac, edited by Veljko Vlahović, was the official publication of the Dimitrov, one of the most famous Yugoslav batallions that integrated the International Brigades.

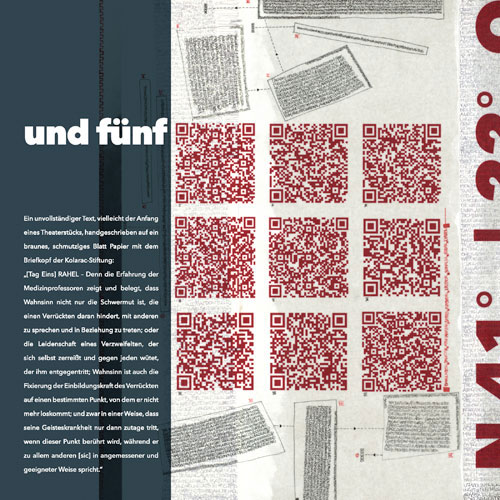

And five. An incomplete piece of text, possibly an entry of a play, handwritten in a piece of brown, dirty paper with the stationery of the Kolarac Foundation: “[Day One] RAHEL – For the experience of the Professors in Medicine has known, and proven, that madness does not consist only in the sadness of a maniac, which prevents him to speak, and deal with People; or in the passion of a frantic person, who tears himself, and wants to offend those who present themselves to him; but as well on fixating the mad his imagination in a certain, fixed Point, to which he remains invincibly bound; in a way that he only shows his alienation when his Point his touched upon, speaking properly and righteously to everything else” (sic).

III. Lazarus

In the Battle of Belchite, the XVth International Brigade managed to secure the Aragon Front, albeit to the cost of heavy losses within the Yugoslav battalions Dimitrov e Đuro Đaković.

The scribbled fragment of a play corresponds, roughly, to a passage from Title X of the Regulation of the Holy Office of the Inquisition of the Kingdom of Portugal (1774). Title X rules the Holy Inquisition procedures in the case of “The Prisoners, who go insane in prison”.

Through inquiring some friends in the Academy of Sciences, I got to learn that in the end of 1941, a group of distinguished prisoners in the Banjica Camp (intellectuals, university professors, scientists, bankers and financiers too, all mostly Serbian), organized dozens of lectures about different topics of their knowing and expertise. The fragment of play might have been performed there, or written to be.

Through other acquaintances among the remaining community of “Serbian of Moses” in Belgrade, I was informed that Mihailo Demajo (or De Maio) was a Sephardic Jew. Born: Smederevo. Father: Isak De Majo, officer in the Army, killed in 1912 in Uroševac by an Albanian Arnanti. Mother: Raža Pinto, born in Subotica, residence in Sarajevo, Banjski Brijeg. Profession: teacher of Spanish. Mihailo volunteered in the early days of the Spanish Civil War. He used his knowledge of Ladino, the language of Iberian Jews, to contribute to the Dimitrovac with poems and, mostly, political commentary

A month after my grandmother’s cremation, we gathered in the cemetery to receive and bury her ashes. According to her will, it seems, I was the one to be handled the small urn and lay it on the grave. After the ceremony, when the small group attending dispersed, the gravedigger approached me and handled a pen case. Inside, cushioned in red velvet, was a small fragment of metal.

“It’s her bullet”, he said, the one lodged in her back since the attack near Ruma in January 1942. The forensics were not sure who called the shot. It was a 9x19mm Parabellum, he continued lecturing, so it could have been after all a German shot, maybe even from the Einsatzgruppe Serbien.”But you never know. The Brits used this calibre in their Brownings”.

The Browning in my grandmother’s box still had a bullet inside. It was nicely engraved: “D1”.

It’s possible that Mihailo Demajo brought an orphan of war from Spain: his Rahel. It’s possible that he canvassed her into one of the ships bound to Eretz Israel down the Danube. And it’s possible that he couldn’t bear the idea of abandon her to a concentration camp after the group was taken from Kladovo.

You never know. Her days were numbered.

Why did you kill me?

„There was a guy who was captured in the war when he was very young. He was held in one of the prisons in Banovina, beaten up daily. But the worst thing for him were the exchanges of prisoners. He was taken severaltimes to be exchanged, unsuccessfully. This was worsethan all the beatings, than the barrel of a gun down his mouth. He had a dream he’d killed someone, he said,I don’t know whether I’d really killed someone, they were shooting at us, we were shooting at them, what happened on the other side I don’t know, but I have a dream of someone coming over to me from the ‘other side’, and asking ‘Why did you kill me?“

Psychiatric clinic patient, Popovača

Tomorrow, today will be yesterday

Thoughts on crossing borders

Susana Moreira Marques

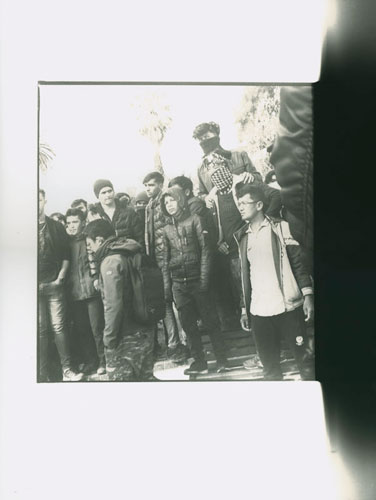

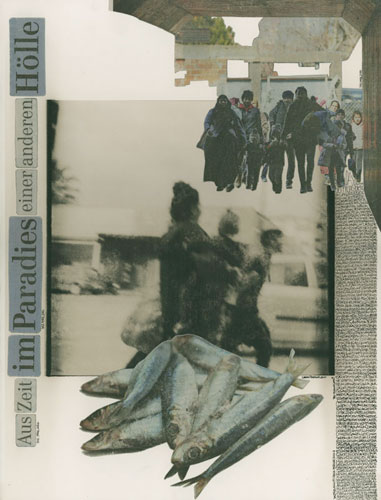

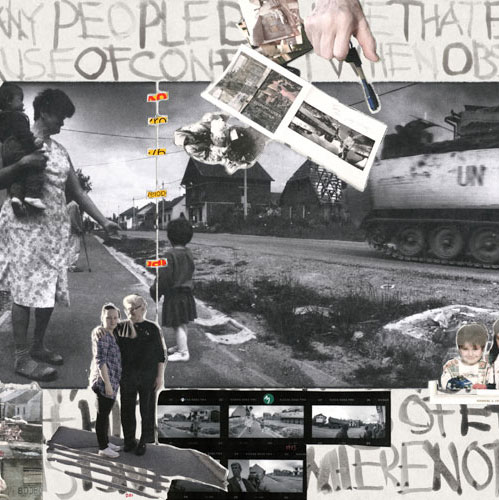

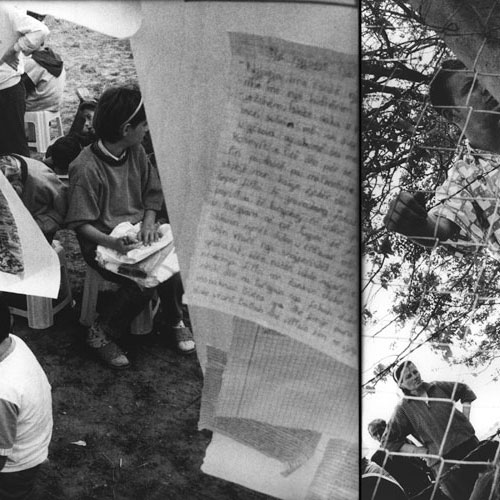

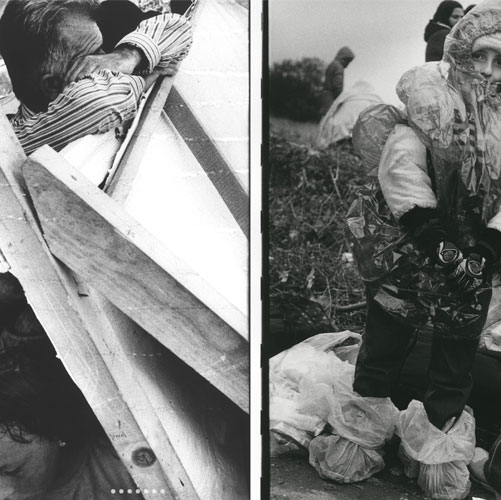

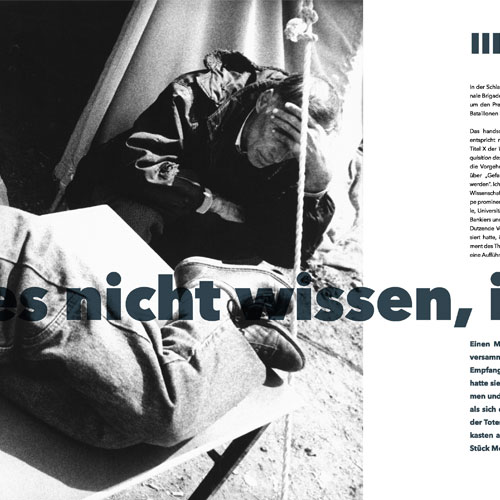

To escape: a verb bringing to mind action, movement, speed, breathlessness. Yet, a great part of escaping is waiting, and perhaps it is that stretch of wait that is too unbearable on the body.

To escape also brings to mind the night and the protection of darkness. But here they are in day light; everything too visible.

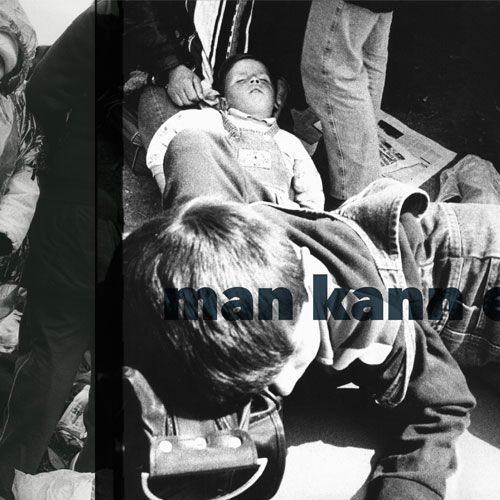

Life, noisily, goes on. Mothers breastfeed their babies to stop them from crying, children find laughing in the minutia of the earth, a stone, a snail, a tree to play hide and seek, men and women chatter, argue, go silent, then sing: some kind of song from childhood, some kind of tune that makes them feel like they know who they really are. At night fall, timid fires give a comforting glow to the sky and bring the thought of lost bright cities. People kiss their loved ones, they make promises to their children; they say goodnight with an unspoken hope for tomorrow.

Think of landscape. Think of how elements come to be attached to one another, how it’s impossible to separate the road from the field, the field from the tree, the tree from the water, the water from the sky. We cannot attribute natural features to the lines we design as we cannot attribute natural causes to the ones dying crossing them.

Every person has a story. Not just a story, but a beautiful, moving, intelligible story. A story with potential to be added to an universal canon. No story is better than the other. The fault lies with the ones telling it, nurturing its way into the world. The task of the storyteller before a crowd – a desperate crowd to be heard – is impossible. One is bound to fail, like a doctor giving up on some to save others.

A man waves – for example that one man, with a sulking child beside him – and we can’t know if he calls for attention or if, on the contrary, he’s tired of looking for attention and he’d like to be able to choose silence.

Think of landscape again and think of the togetherness of crowds. That swell of people, with its seemingly incomprehensible organic rules, is impressive but not unfamiliar. The collectiveness of fear, of survival, and the most acceptable inertia, is only too familiar. We’ve seen before how people can be horded and the ones braking from the horde, irretrievably lost.

Soon, what we see daily – the new, the news – will be a memory. It won’t stop hurting because it’s a memory, not for the ones who lived it. For us, watchers, it will be history, told in a certain way, with the forgiving distance of the generations.

Movies will be made, actors, directors, eloquent public figures will make speeches about how civilisation won’t let violence, despair or pure indifference happen again. We’ll be driven again by the unshakable intuition that our children will be better than we are.

I observe closely my hands, thinking of how so many other women are, at this precise moment, observing their hands. I observe them closely for signs of aging, spots, scratching looking bits of skin, I look for proof of a loss of strength. (I have always failed to observe what remains the same – the lines of the palm – since, for very private reasons, I’ve always been skeptical about what our bodies predispose us to.)

Every woman keeps a close observation of her hands and knows that every thing she does, every job, every child bore, every man loved, every person cared for, every bag carried with remaining belongings; every gesture made will show in her hands.

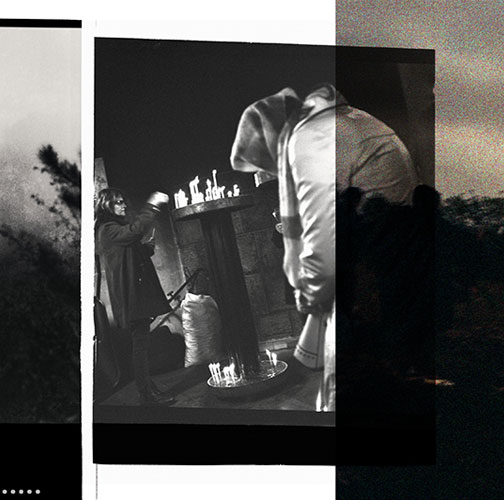

Even to cross to the other side of life – that is, death – it has been said that you need to pay. It has been said that not even hell is entirely free. Someone will collect something from you, if not a fee, maybe a word or a sign, maybe a sacrifice.

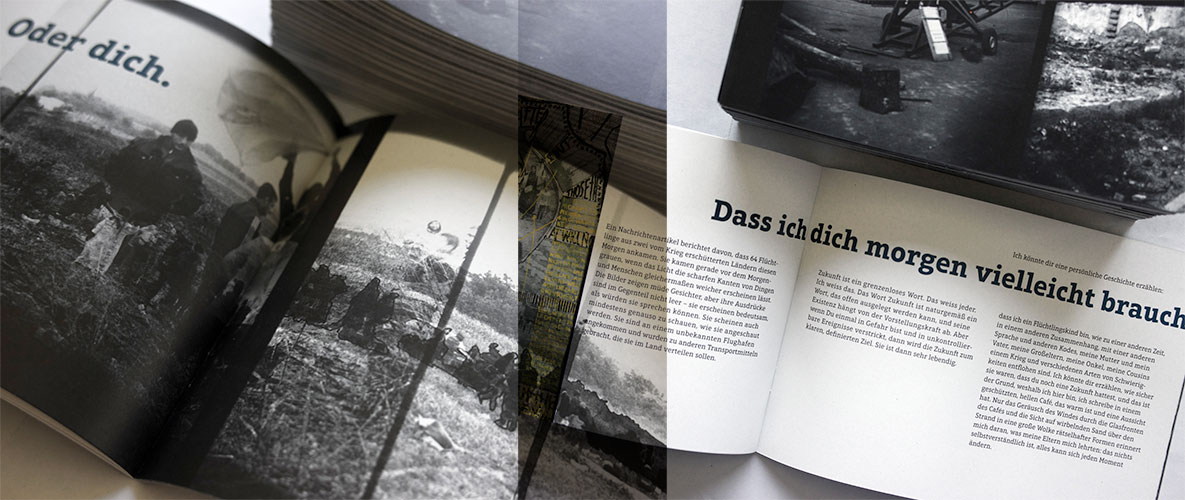

A newspaper report says 64 refugees from two war-torn countries arrived this morning. They arrived just before dawn when light smooths all sharp borders from things and people alike. The picture shows tired faces, but their expressions are not emptied – on the contrary, they seem full of meaning, they seem to talk. They also seem to look at least as much as they are looked at. They arrived at a discreet airport and were taken to other transports to be taken to several parts of the country.

„Future“ is a borderless word. Everyone knows that. I know that. „Future“ is a word by nature open to interpretation, its existence depends on imagination. But once you are at risk and are trapped in uncontrollable events, the future becomes such a clear, well defined objective. It’s very much alive then.

I could tell you a personal history: of how I am the child of refugees, of how, in a different time, a different context, with a different language and different language codes, my mother and father, my grandparents, my uncles, my cousins, fled from war and difficulties of various kinds. I could tell you how much they were sure they still had a future and that’s why I’m here, where I am now, writing in a shielded, bright cafe, warm and with a view. Only the sound of the wind through the cafe’s glass paneled walls, and the sight of a large cloud swirling fast in mysterious shapes above the sand of the beach, remind me of what my parents taught me: that nothing can be taken for granted, that anything can change at any moment.

That tomorrow I might need you.

Or you.

Or you.