former Indian Subcontinent

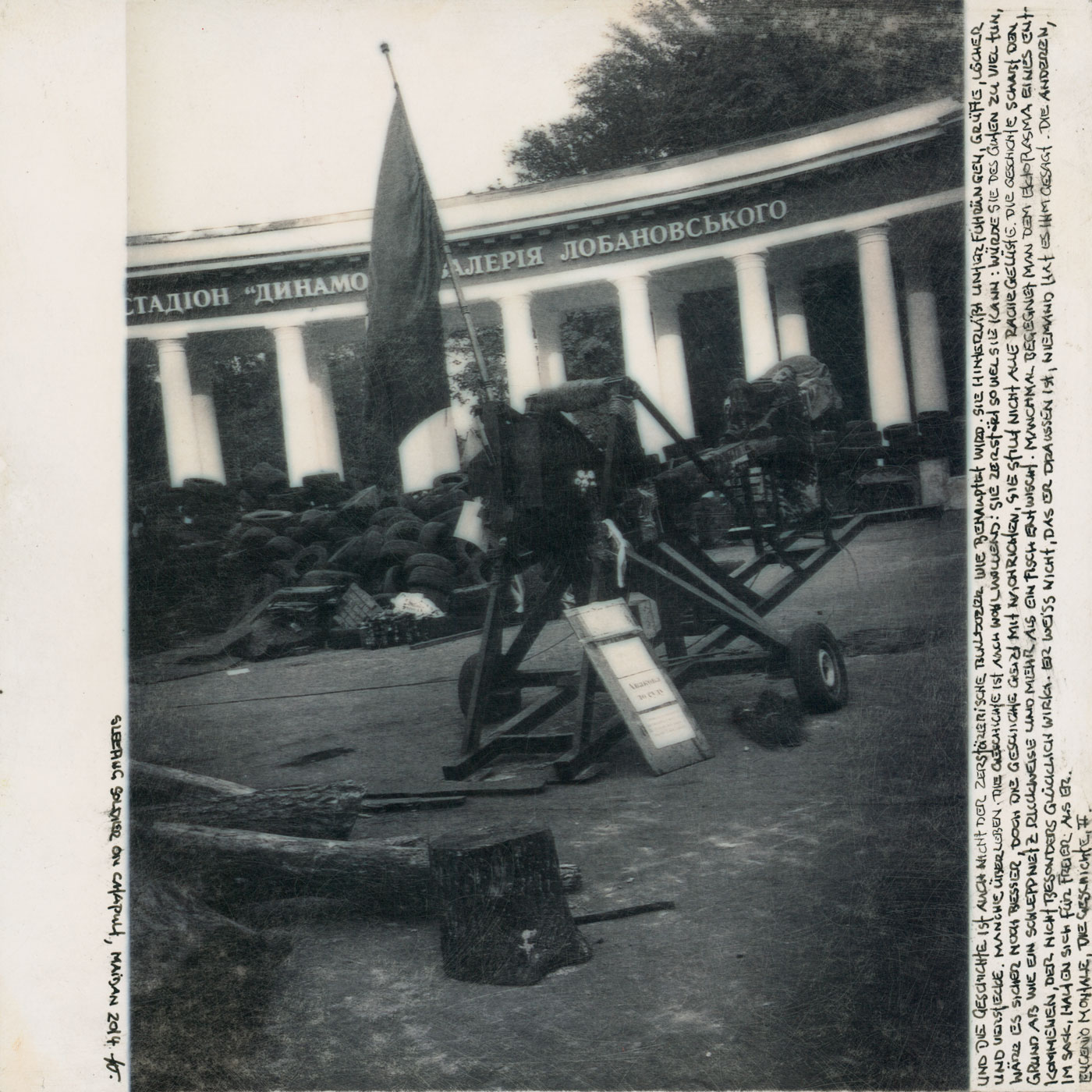

bookproject – first draft with blindmaterial

former publications after Hannah Höch

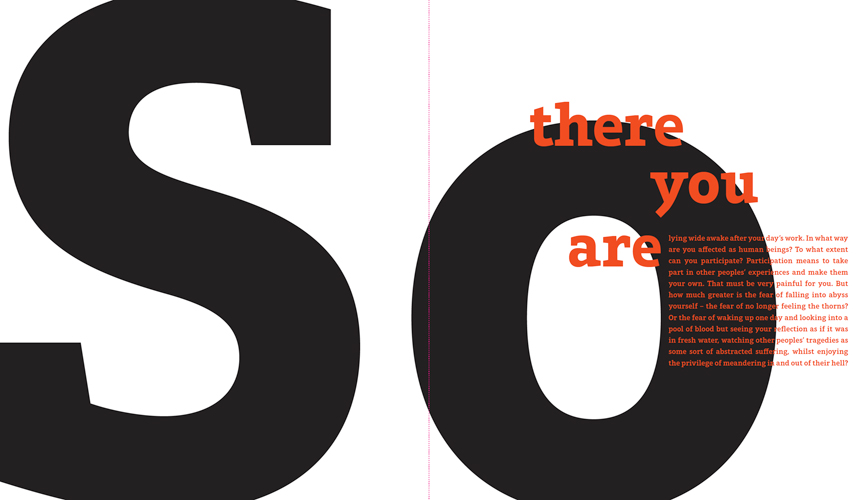

dialogue Mendes|Dinić

„

…

My interpreter had six children. From newborns to grown-ups, like a staircase. It was still possible when we arrived to the village to see where Dostum’s had crushed the children’s skulls. A stain… It looked like the victims had been grabbed by their ankles, or so I guessed, because one could still see purpled marks of hands printed on the babies’ legs. The heads… Just like that. Young skulls are soft. I entered one of the houses and there was the body of a girl. I couldn’t exactly understand what happened with her since her dress was folded back, covering her head. I mean, the place of her head. My interpreter cried out, desperate. He cried and cried and cried. I walked outside and raised my hands high:

how? How?…

…

“

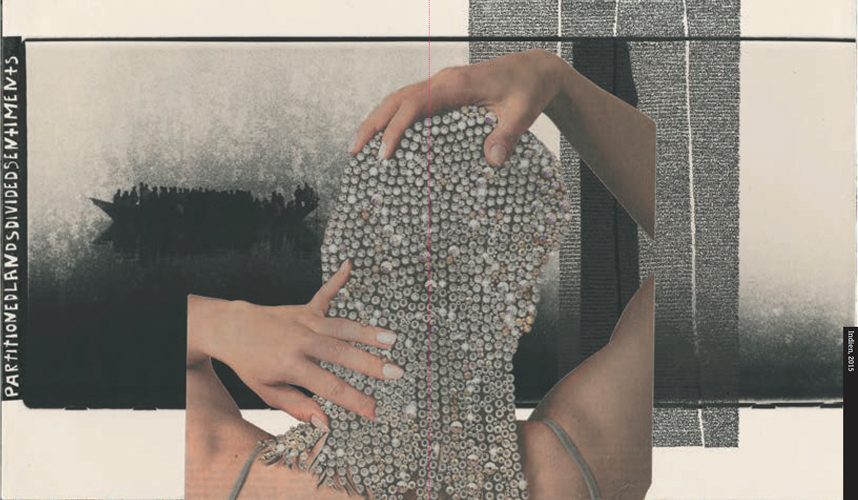

How is the key question in art. In the search for form, the artist must ask the question of how? How is the natural predecessor of form. The form is as such cold. Form is an experiment. To augment form with content is a further level in artistic creation. To have found a universal language is already a culture.

An example: children are not a form, they are a part of the story. In them is to be found the culmination of people, place, events, both happy or sad, dependent on whether these events themselves are happy of sad. Children can viewed as being of a tapestry of content.

Heads and skulls are forms. In them, nature tries to answer the question of how, without articulating the question aloud. In a similar way, a dress is a form, an organ pipe, the number 6 or a scream, a scream, a scream.

The forms holds the content together like purpose-built mould. The artist is a carpenter and collector. All stories are collected, rub against one another, are assessed – the art learns from itself about itself. The art is smarter than all of those who created the mould. If the mould breaks, then our story breaks too. Culture – nowhere.

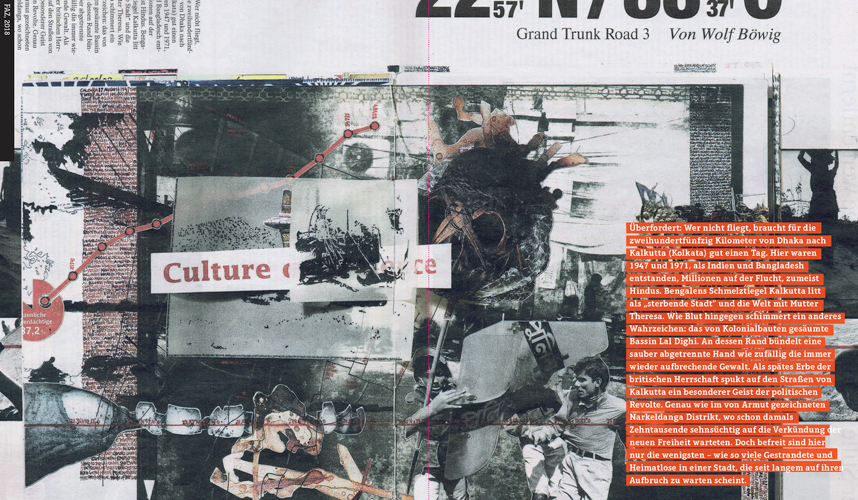

FAZ facsimile – essay Habbo Knoch

dialogue Mendes|Dinić

„

…

the rebels made him look for and find his father, after which they put the infant on top of his corpse and declared the boy ‘Prince of the Dead’.

…

“

In the year that the boy named Morie ascended the throne and become the Prince of the Dead I was 14 years old.

Some years previously, the ground shook. Bombs fell on my hometown. I did not understand what was happening and the grown ups just grimaced – that was a sign of the times. The child looked at the world in its normal way. We and they were not concepts but words. And until someone consented to explain the words to us, we we could not speak with our neighbours, our dealers in death. At 14 years of age, we had just moved west, I knew all of the words by heart. But nobody was there to warn me about them. Words are in fact contaminated bodies, capable to making the ground shake and able to murder my neighbour. Words cause people to be shot at.

Morie, the boy on the cruel throne, who was previously his father, knew, or, at least today I imagine it to have been so, today, as I try to use words to shut words up, Morie understood the capacity of words, even before he found someone to explain them to him. Early enough, he got to know the people, the horror with which he weighed his words: „Prince of the Dead“. Just one more installment in the lineage of the killers of our parents with them their history, their faces and their culture.

Or do our parents not have the faces of their butchers?

concept and visual artwork: Wolf Böwig

text: Marko Dinić, Pedro Rosa Mendes, Habbo Knoch

layout: Christoph Ermisch